Well engineers have tried to couple both of these worlds into want is commonly called VTOLs, short for Vertical Take-Off and Landing Vehicles. While helicopters fall into this category, we are not going to talk about those in much detail. We are going to talk more about airplanes that take-off without the need of a runway; or with a very small one. Some airplane, especially fast and heavy ones, need very long runways in order to generate enough lift to take-off. This can be problematic, since there isn’t always a wide and long runway to use. We are also going to talk about STOL, where the S stands for Short.

Let’s first start by explaining why would we have the need to have planes that can take-off vertically, when we already have helicopters? Helicopters are good at taking off vertically, but then planes are more efficient: they consume less fuel per kilometre, they can go further, and they can also go much, much faster. All of this is important sometimes, for military purposed for example. Fighters must be fast, to do interceptions, and generally to have the fastest response time to any in air issue. Ground attack airplanes and bombers have to be able to fly either low or very high, and need long ranges, not always possible with helicopters.

But, they all need runways, which in case of war is something very complicated to preserve. Taking out a runway is a very efficient way to prevent a huge number of airplanes to operate. Helicopters can land pretty much anywhere, they only need a (roughly) flat surface, hence can land on a relatively small ship, in remote places, or from a destroyed runway. So naturally, engineers have thought of different ways to combine the vertical take-off capabilities of helicopters, and all the better performances of airplanes.

The idea of an airplane that can take-off and land vertically has pretty much always been around, some patents and ideas go back all the way to the 1920s. But things really start getting serious in May 1951, when Lockheed and Convair are given contracts to build VTOL prototypes. Lockheed would go on to make the XFV “Salmon”, and Convair the XFY “Pogo”.

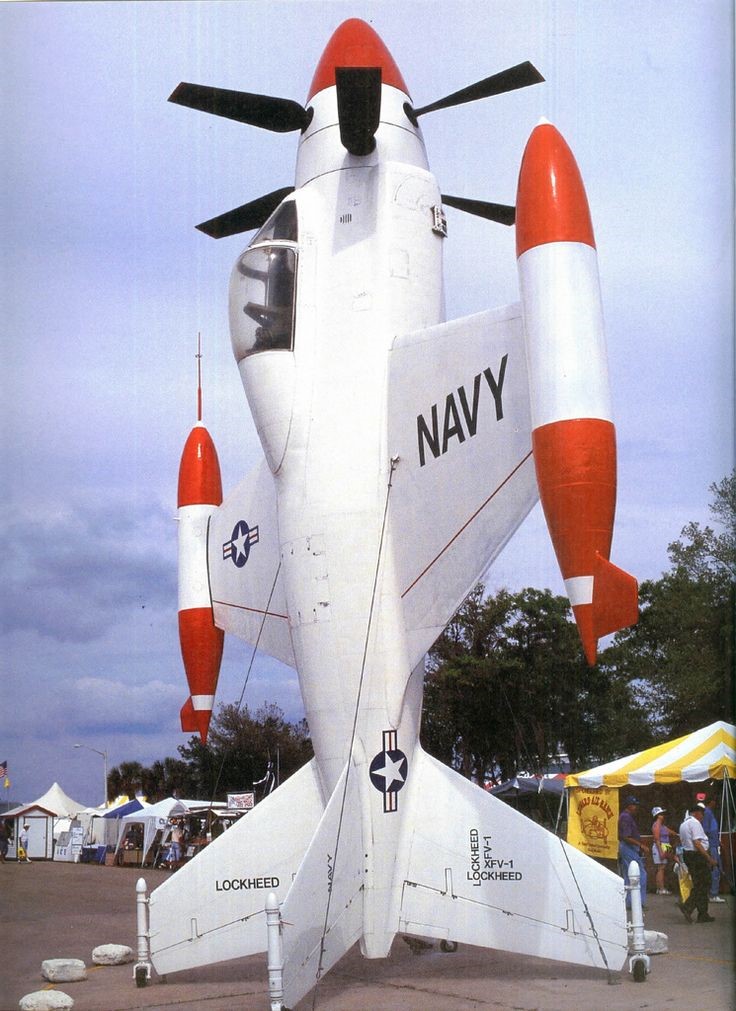

A picture of the only flying XFV, build by Lockheed.

Lockheed went on to build the tailsitter (which is pretty self-explanatory: a plane sitting on its tail) airplane. For testing the horizontal flight segments, it was fitted with a non-retractable external landing-gear, giving it an even more atypical look. On the total 32 tests that were done, none were done to test the actual VTOL capability of the aircraft.

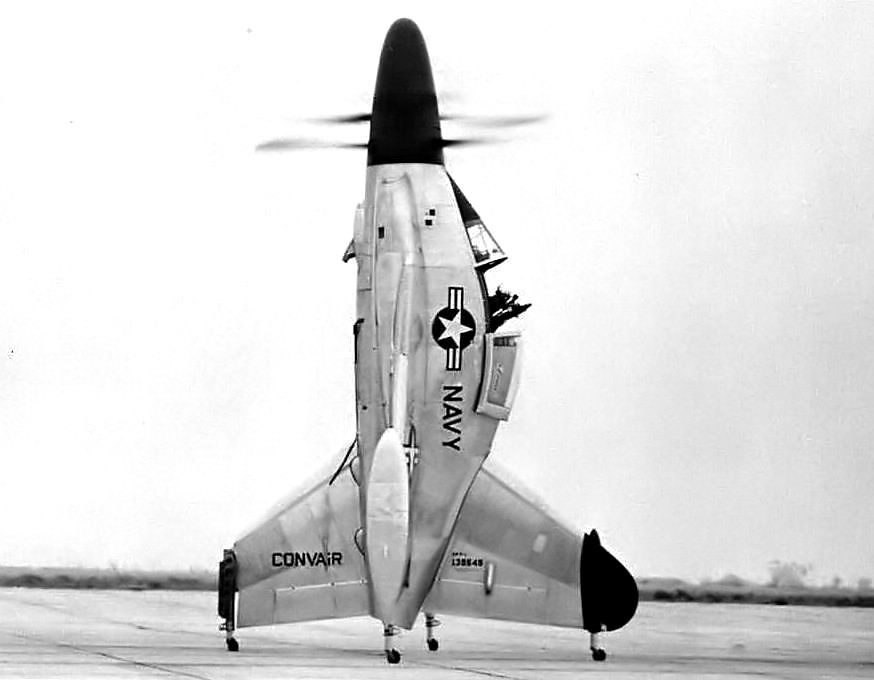

On their side, Convair build the (also tailsitter) FXY “Pogo” (this nickname was given to the prototype, referring to a pogo stick, that bounces up and down around its longer axis), which did more tests then the Lockheed prototype. Since this had never been done before, for the first test of the vertical take-off capabilities of the aircraft, the propeller hub protection was taken away and a tether was attached to the plane, to prevent the pilot (and the actual plane) from being hurt and damaged. A series of cables was also holding the airplane is case of any loss of control.

After multiple tests, the prototype went on to do outdoor testing, and they managed to do the first vertical to horizontal flight conversion in November 1954. But after more testing, the airplane started to show flaws: it was very hard to land, as the pilot had to turn around to see where he was going; and it was hard to slow it down. So the hope to equip most ships with this type of fighters soon vanished. It needed the most experiences pilots, which could not allow for a wider use of the prototype.

The XFY “Pogo”, looking very similar to the XFV. Both are tail sitters, with counter-rotating propellers

Nowadays, other than helicopters, there are two main types of VTOL aircrafts: tiltrotors and directed thrust airplanes. Since the designs tested in the 50s didn’t convince much, we turned to other ideas, in hope to make this dream a reality.

Let’s first start with tiltrotors. The most known one is by far the Bell V-22 Osprey. It is considered to be the world’s first production tiltrotor aircraft in the world, with about 220 build to date.

When in flight, the V-22 simply looks like a plane with simply bigger propellers then usual…

The Osprey is the example taking best of both worlds, VTOL capabilities of a helicopter, and long range of an airplane, and combining them together. The V-22 is capable of ranges nearly twice as long as other helicopters can go one and a half times faster, and nearly as much higher. So it’s of great use, especially for the Marines in the US military.

…Only when it lands or takes-off does the V-22 show how different it is

But, this comes at a costly price. The V-22 is a very controversial project, because there have been numerous crashes, and deaths during its production, and use. It is also a very expensive and complicated machine to maintain and operate. Even if it gives a lot of benefits, it has some big flaws. Having a very reliable machine, simple and cheap to maintain is also something very important in the military.

Moving on to thrust directing airplanes, the most common is without a doubt, the most famous VTOL airplane, the Harrier. The Harrier is a unique airplane, because it changes the direction of the thrust, directing towards the ground when taking off, and gradually moving it 90 degrees towards the tail of the airplane, as a conventional plane.

When near the ground and using its VTOL capabilities, the heat generated by the engines can be clearly seen

Though the Harrier can take-off and land vertically, it doesn’t do it very often, as this consumes a huge amount of fuel, meaning once in the air, it only has a limited range, or can take less weaponry or payload in general. This is why the Harrier uses STOL, to assist it while taking-off on short runways, on smaller carriers. The thrust is directed roughly 45 degrees, to help the plane gain both altitude and speed, enabling it to take-off on short distances.

Other than military, some ideas for commercial VTOLs have emerged, but none have been further than a simple idea. Though with electric engines being more affordable and batteries are more efficient, some have come up with electric VTOL cars. These have only been (successfully) tested, but only the future will tell if “where we’re going, we don’t need roads”.