Disbelief, shock and bewilderment surged through the people of Britain as newspapers reported the nation was at war with Germany.

Nearly 100 years ago, on 4 August, 1914, when that fateful declaration was made, the events came as a total surprise to everyone outside the senior military.

Leaders of industry felt the shock just as profoundly, not least Frederick Henry Royce, the Engineer-in-Chief of a successful manufacturer of luxury automobiles. Rolls-Royce board members, meeting in emergency on 7 August, feared the company’s bank would refuse to support an expensive luxury product at this time of war and call in the overdraft on which the business depended. Drastic measures followed at once. They would halve the company’s workforce, halve the hours the remaining staff could work – and refuse any government request to switch to aero engine work of any kind.

But the company quickly changed that third policy. Within days Royce and Claude Johnson, the company’s General Managing Director, had been called to a meeting with the head of the Royal Aircraft Factory, responsible for supplying military aircraft, who had convinced them to tender to build a batch of Renault aero engines.

Perfection

Another emergency board meeting agreed to the plan, in the process unknowingly opening a far-reaching new era for the young Derby-based company.

Fifty-one-year-old Royce, whose foresight, passion for perfection and technical genius had already made his company a world leader in automobiles, immediately threw himself into this daunting new challenge. He faced immense difficulties: his poor health (worsened by his relentless urge to work as hard as possible), the ensuing need for him to work remote from the pressures of the factory (in a healthy seaside location 300km away, supported only by a small team); and a total lack of experience in the field of aero engines.

Typically, Royce was less than impressed when he first reviewed the design of the Renault engine before his company began to construct an initial batch of 50 that were needed urgently to power British B.E.2 light bombers.

Heavy, low-powered and fuel- and oil-thirsty V8 with cast-iron cylinders and air cooling, the Renault 80 horsepower (hp) unit convinced and at the same time inspired Royce to develop a far better product; one that would be water-cooled to provide a much higher power-to-weight ratio than Royce had ever achieved before.

The company’s board quickly agreed with his proposal and, within just one month of the outbreak of war, Royce had agreed to a military plea to develop a new 200hp aero engine and had already sketched-out a V12 design. This was based partly on proven characteristics of the company’s successful 40/50hp car engine and partly on a German six-cylinder DF80 aero engine Rolls-Royce had acquired earlier in 1914 for detailed examination (Mercedes had plans to develop it for use in rival luxury cars).

Lighter and better cooled than rival aero engines, the promising DF80 had recently set new aero records for endurance and performance in Germany. It included technical advances such as forged steel cylinders and water-cooling jackets of sheet steel, technologies that Royce rapidly incorporated in his new V12 design.

Four weeks after war starting, the company’s board agreed to build two experimental V-engines at a cost of about £1,500 each (some £120,000 or $200,000 today), a technical and commercial risk justified in the board’s view, believing ‘that if such an engine were placed before the Government orders would immediately ensue’. At the same time the company reinstated all its shop-floor and clerical workers because the bank had agreed to finance the new project, patriotism proving an effective driver of new business initiatives.

By October 1914, Rolls-Royce was fully committed to aero engine work, with development underway as well on two smaller derivative engines. All later gained names of birds of prey: Eagle for the big V12, Falcon for the smaller 150hp V12 and Hawk for the 75hp in-line six-cylinder unit, effectively one bank of the V12 Falcon.

Confidence

Work on the Renault engine continued but its low-tech specification meant it would never match the performance of the high-flying Eagle, first orders for which came at the start of 1915 (for 25 engines at £930 each, or £75,0000/$123,000 today) to power 12 Handley Page O/100 twin-engined patrol bombers. The confidence the UK military showed in this new engine, still at the drawing-board stage, was undoubtedly influenced by its experiences with rival manufacturers, whose aero products had varied from under-powered and unreliable to expensively disastrous.

Anxious to avoid similar problems, Royce urged his engineers to put maximum effort into effective bench- and flight-testing, while continuously striving to improve reliability and increase performance. The Eagle made its first test-bench run at the start of March 1915 and within two days it achieved 225hp, exactly the target figure Royce had set just six months earlier – and 12.5 per cent more than the military had contracted for.

Pressure

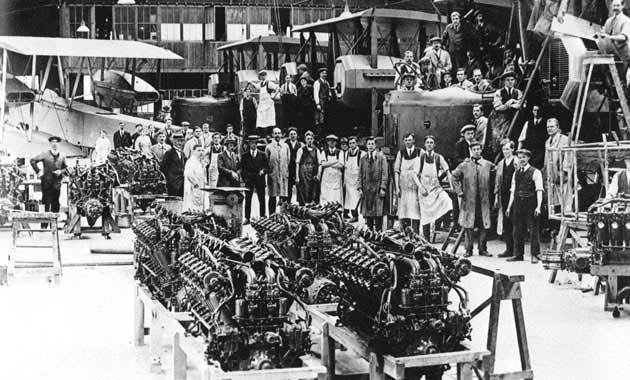

As further Eagles joined the programme Royce cranked-up the pressure on rival engine suppliers, testing engines ruthlessly to discover the weakest components and designing and proof-testing replacement parts. Engineers purposely mis-handled Eagles to induce major stresses in a relentless campaign to create a reliable and mission-capable product that would serve effectively in arduous combat roles. Industry-leading innovations such as aluminium-alloy pistons (replacing steel) continued to increase the Eagle’s power potential and by December 1915 the engine flew for the first time, in the Handley Page O/100 bomber – less than 16 months after getting the go-ahead.

Due to the wartime requirements, Britain soon began to need many more Eagles. War Office officials tried to persuade Royce and his senior colleagues to agree to other UK manufacturers sharing production, something they stoutly resisted (although they gave the Brazil Straker of Bristol approval to build Eagles and Falcons), gaining instead a big expansion of the Derby factory.

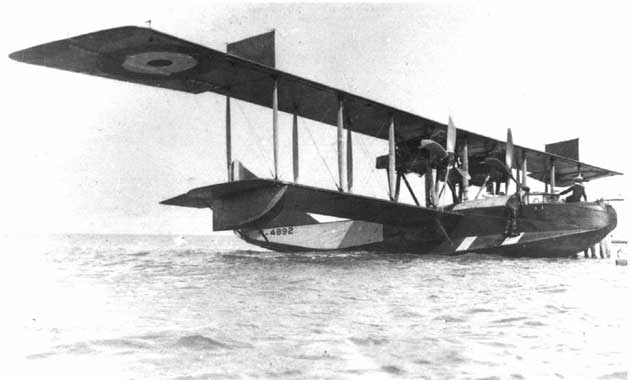

This was timely, for in June 1916 Eagle found a second application in the Curtiss H12 flying boat – soon followed by the vital role of re-engining and enhancing the FE2d fighter. Installation of the Eagle in the Airco DH4 light bomber made it faster than enemy fighters.

Curtailed

By 1917, against future plans to launch a British bombing campaign on Germany in 1919, vast additional numbers of Eagles were ordered – but the end of the conflict in 1918 curtailed much of that work, by which time some 2000 Eagles had been produced. Overall, this pioneering V12 – an engine in which, ironically, Royce warmly embraced effective technologies developed in Germany for the DF80 engine, while the smaller Rolls-Royce Falcon and Hawk also gave vital service.

Famously, the engine designed for the darkness of war gained its final accolade with an epic achievement seven months after the Armistice. Piloted by John Alcock and navigated by Arthur Whitten Brown, a Vickers Vimy IV powered by two Eagle VIIIs won headlines worldwide with the first non-stop flight across the North Atlantic, taking off from Newfoundland, landing in a bog in Ireland and earning its crew knighthoods for their achievement.

History also notes how Henry Royce’s devotion to technical excellence in the Eagle would lay the foundations of engineering experience and technical strength that empowered the creation of the most successful aero engine of the next world war – the Rolls-Royce Merlin.